Alexandru Călinescu’s private collection includes books and periodicals of Western provenance, which could not be obtained from bookshops in communist Romania, but only by way of clandestine channels, with the help of the few people who could travel back and forward across the Iron Curtain. In addition, Alexandru Călinescu also kept materials connected with the student magazine Dialog, in which, under his direction, articles were published that were nonconformist and subtly critical of the Ceauşescu regime. A great part of the collection disappeared without trace after it was confiscated by the Securitate in 1983, but its absence is immortalised in the minute of the house search. The story of the growth and diminishing of this collection has its origin in Alexandru Călinescu’s passion for literary journalism, which developed from his student years and later combined harmoniously with his professional life in one of the most important university cities of Romania. His journalistic debut is suggestive of the changes going on in the world of literary magazines in the second half of the 1960s. On the one hand, publications that had enjoyed great prestige in pre-communist Romania returned to the foreground at the expense of journals founded after 1945. On the other hand, publications in the literary field also proliferated due to the growth in the number of those professionally qualified to produce such magazines, as a result of the increasing student intake of higher education in the humanities. At the same time, Alexandru Călinescu’s entry into the world of literary journalism also coincided with the period that is nowadays considered to have been the end of the cultural liberalisation of the 1960s, but which at the time seemed to be no more than the beginning of the de-ideologisation of Romanian culture and its re-orientation towards the culture of Western countries, especially French culture, which had been a traditional source of inspiration in Romania from the nineteenth century onwards. In short, the late 1960s were perceived by the majority of Romanians as a period of hope. Especially young people at their literary debut thought that they had before them a career which they could construct on their own, becoming better and better professionals and not politruks ever more obedient to the Party. “My first experience connected to the press took place when I was in my last year of university (which at the time was five years). Already in my second year, I had begun a collaboration with Iaşul literar, at the time the only cultural magazine in the city. In 1968, one of the editors of the magazine left to do his military service, and I was proposed to stand in for him, probably on the grounds that I was a ‘promising young man.’ I did this for six months, from February to July. It was an interesting experience, especially as the head of the criticism section, where I had been ‘posted,’ was Dimitrie Costea, a cultivated and demanding person, from whom I learnt a lot. But Costea was in conflict with the editor-in-chief of the publication, a former worker promoted by the Party, and this conflict sometimes resulted in very tense moments. It was not the ideal atmosphere, but, all in all, it was a period that I recall with pleasure, especially as things had suddenly become easier for me financially. I had my editor’s wages – the minimum salary, but it was still something – plus pay for my monthly collaboration, to which were added two university scholarships – the standard scholarship and a scholarship for merit – all of which added up to a nice sum. Newly married, I could – I mean, we could – afford little ‘extravagances,’ including a holiday at the seaside. I continued my collaboration with Iaşul literar, which later merged with Convorbiri literare [Literary conversations – a journal with a distinguished history, originally founded by the Junimea literary society in Iaşi in 1867], and then I became a contributor to the newly founded Cronica, a weekly magazine with a broader cultural profile. I had regular columns in both from 1971 to April 1989 [when he declared his support for the open letter of the seven Bucharest intellectuals who contested the policies of the Ceaușescu regime in the field of culture]. I also did the literary chronicle in Convorbiri and later in Cronica. It was a sort of gamble, as it was hard to maintain a weekly chronicle. Unfortunately I wasted a lot of time reading mediocre or even bad books and I smoked far too many cigarettes staying up till two or three a.m. because I had to hand in the chronicle the next morning,” says Alexandru Călinescu of his beginnings in literary journalism.

Then major conflict with the communist authorities that radically changed Alexandru Călinescu’s life broke out because of his collaboration with another publication, the Iaşi student magazine Dialog. As its editor-in-chief from 1981 to 1983, he managed to attract to the magazine the most talented among his young colleagues and students, whose mentor he implicitly became. Alexandru Călinescu characterises the context in which this magazine appeared and its specific character as follows: “I arrived there in the spring of 1972; I was a young assistant lecturer. I was called as a diplomatic solution to resolve a conflict. I was editor-in-chief until 1983, immediately after the Securitate investigation. It was a lively magazine, very lively in comparison with what the press was like at that time. In the early 1980s an outstanding generation of graduates appeared, who caused the regime a lot of trouble: Luca Pițu, Dan Petrescu, Sorin Antohi, Liviu Antonesei, Dan Alexe. The magazine Dialog came under the observation of the authorities on the grounds that articles of a subversive character were published there. To tell the truth, this was indeed so: such texts were published. All their [the Securitate’s] accusations were based on reality. We had forbidden books, forbidden periodicals; in the magazine that I was in charge of, texts were published that were not to the liking of the communist regime.” As editor-in-chief, Alexandru Călinescu was directly responsible for the ideological content of the publication, according to the new press law of 1977, resulting from Decree no. 471/1977 for the modification of the Law of the press in the Socialist Republic of Romania no. 3/1974 and Decree no. 472/1977 regarding the ceasing of the activity of the Press and Printing Committee. According to the new legislation, the censorship committee, the so-called Press and Printing Committee, no longer existed, but censorship was turned into self-censorship by making those in charge of publishing houses, the editors of publications, and the national radio and television stations responsible for keeping the content of books, periodicals, newspapers, and radio and television broadcasts in conformity with official ideology. In this context, the criticisms in the articles in Dialog could not be expressed openly, but were camouflaged by coded language that could not be easily spotted by the reading public, but was addressed only to those with a relatively high level of general knowledge. For example, few would have recognised that the ironic description ‘the hirsute epigones of Hegel’ referred to the founding fathers of communism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. And in any case, their works were little known and understood in Romania, where there was very little tradition of authentic leftist thought, with the result that the two authors were studied primarily through the intermediary of Lenin’s reading of them. What anyone could grasp, however, including the Securitate’s “sources” of information, was the fact that the bibliographic references attached to the articles in question showed that their authors were up-to-date with what was being published in the West in their field, in spite of the cultural autarky and the implicit restrictions on the official importation of foreign books that had been imposed by the Ceaușescu regime through the so-called Theses of July 1971. These references were in fact inventories of collections of Western books and periodicals, unavailable in bookshops in communist Romania, but which the authors of the articles had managed to procure clandestinely, so that they constituted veritable private libraries of nonconformist publications, circulating by informal channels among those interested in such reading.

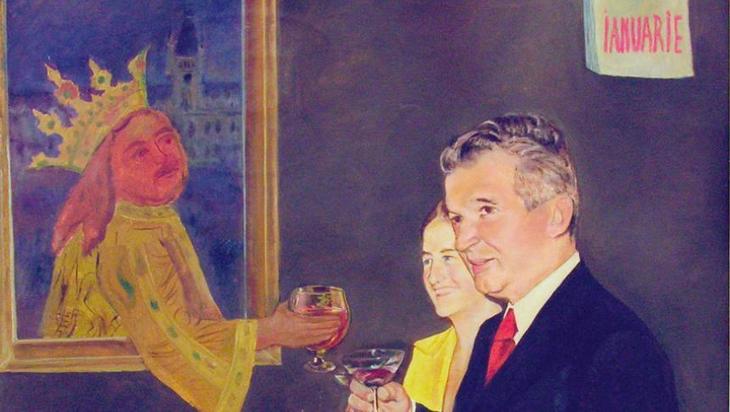

Despite these evident facts, the magazine Dialog continued to public such articles for a time, as the public to which they were addressed was basically limited to the students of Iaşi, which was, after all, a provincial city. In the way in which the communist authorities treated Dialog, its editor-in-chief Alexandru Călinescu, and those who published in the magazine, there was a turning point: May 1983. As Alexandru Călinescu recalls, the coordinates of that context were the following: “What brought everything to a head was the following fact. Theoretically, our magazine was supposed to be monthly, so with twelve issues per year, one each month. However there was no obligation for it to be so, and thus we could publish nine issues, or ten, on the grounds that in some months it was vacation. We tried, and we often managed, to skip the anniversary months: January, because Nicolae Ceaușescu’s birthday was on 26 January, and August, because the national day of Socialist Romania was on 23 August. With August it was easier, because it was vacation. With January it was harder, but we ‘got round it,’ so to speak. In January 1983, the fateful year, we didn’t manage to trick them, and we were ordered to bring out the magazine.” The problem that all publications had to face in January concerned the way they represented the celebration of the birthday of the secretary general of the Party. Most publications competed with one another to make the most ingenious contribution to the personality cult, with articles full of eulogistic epithets and glorious images. Any avoidance of this routine of the personality cult was implicitly suspect. The solution found by the staff of Dialog to get out of this situation was very ingenious, as Alexandru Călinescu recalls, but at the same time it was what generated the later collision with the Securitate: “The problem was with the cover of the magazine: a painting by Dan Hatmanu, in which Stephen the Great [leaning out of a painting on the wall] is clinking wine glasses with Nicolae Ceaușescu [standing in front of the painting with Elena Ceaușescu]. Well, this was our choice for the first page. I met the artist and spoke to him about the picture, expecting him to give me a complicit wink, meaning that he had been ‘taking the mickey’ out of Ceaușescu. But he was serious and he told me that the Ceaușescu couple had been very pleased with it. Then we put the picture on the cover, but the people in my team at the magazine boasted that we were printing such a kitsch cover as a joke, to laugh at the Ceaușescu couple. And word got around in the city that this had been our intention. Well, a short time later, things got extraordinarily agitated in the Faculty, with the Securitate people going around asking questions all over the place, thinking that something was being published as a mockery. The magazine came out with that cover – there was nothing they could say against it – but the idea remained that this issue of the magazine had been brought out in mockery. The idea remained that we had published a caricature. Although, as I said, the artist was absolutely serious when he painted the picture.”

It was not just the cover, obviously ironic, of this magazine issue of January 1983 that triggered radical action against the opponents of the communist regime in Iaşi, but also the special connections that they had with foreign language assistants at the University there. Alexandru Călinescu and many of the contributors to the magazine Dialog had close and lasting connections with these assistants, who could circulate freely between Romania and the West and were one of the sources through which the intellectuals in Iaşi could procure foreign books that were not available from bookshops in Romania, books to which they then made reference in their articles in Dialog. Books and periodicals brought by these foreign assistants or by people from Romania who managed to get the Securitate’s approval to visit Western countries formed the nucleus of the collection of publications procured clandestinely by Alexandru Călinescu. The great majority were books that could never have been translated in communist Romania due to their content’s not being in conformity with official ideology. Each of those in the group associated with the magazine Dialog had their own sources of these books, but they all had one source in common: the foreign assistants. Each would order different books, so their collections of clandestine publications complemented one another. These books and periodicals then circulated among all the members of the group so that they could all keep as up-to-date as possible with what was being published outside Romania. “They [the Securitate] knew that we had books that circulated, discreetly, among us. Periodicals, newspapers – which the French assistants brought me. Dozens of such periodicals and newspapers. They brought us books too, of course.”

The event that effectively triggered the 1983 Securitate investigation was the interception of a letter sent by Dan Petrescu through the intermediary of one of the French assistants to Ioan Petru Culianu, his wife’s brother. Culianu had emigrated illegally many years before, but he had constantly followed what was happening in the literary world of communist Romania, and the letter in question was an update full of humour on the latest developments in the field. In his letter, Petrescu told among other things how the team at Dialog were trying to make a mark through their professionalism, but were held back by those who had won their prestigious positions on the basis of obedience towards the official ideology rather than professional value, and whom he characterised as “a gerontocracy of zero value, but which survives by playing the game of power, allowing itself to be manipulated, so that when the politics are not up front, they are disguised as literary politics, which consist especially in decapitating anyone who tries, on different, true, bases, to raise their head, and in the careful selection of their successors, of individuals who to this end have offered convincing proof of platitude, conformism, and lack of character. Censorship,” Dan Petrescu continues, “no longer exists, officially, which paradoxically makes it all the more drastic. […] Someone was nostalgically recalling to me the days of Stalinism, when you knew pretty much exactly what you were supposed to write. […] While nowadays, he lamented, […] no one knows anything; you can write something completely neutral and find yourself under accusation; the arbitrary reigns everywhere.” It was the content of this letter than never reached its destination that provoked searches at the homes of the publishers of Dialog, starting with Alexandru Călinescu.

In the course of their search on 18 May 1983, the Securitate confiscated various materials from Alexandru Călinescu’s private collection, some on the grounds that they had an anticommunist theme or character, but others simply because they were in foreign languages. What was confiscated on that occasion from his collection of foreign books and periodicals, procured clandestinely through the intermediary of foreign language assistants and other people who were able to travel to the West, was never returned. Alexandru Călinescu only managed to save a few books from his bookcase at home by putting them in his son’s schoolbag. The fact that the materials confiscated during this search were selected absolutely chaotically is also clear from Alexandru Călinescu’s own account of the incident: “Why did they come? To make a search because there was information that I had documents and papers of a hostile character towards the Communist Party and the communist regime. As far as the books that were not approved of by the communist regime were concerned, they were tricked in a way, because my library, almost all of it, wasn’t in the apartment where I lived but elsewhere, at my mother’s. […] I had files with texts from the magazine Dialog that I dealt with and that was a target of theirs. I also had a caricature there that seemed problematic to them. I remember it was with Brezhnev laughing from ear to ear and reading The Gulag Archipelago. […] They also confiscated two novels from Henry Miller’s trilogy – Nexus and Plexus. I didn’t have Sexus at home; I had lent it to someone. In the investigation I asked why they had taken them, and they replied that in Miller’s books there were some details about freemasonry… They also took eleven cassettes of music. I made a fuss about those, and later they gave me them back. There was nothing compromising in the eyes of the regime on them – it was the music my children listened to.”

As a consequence of the investigation that followed, Alexandru Călinescu was excluded from the magazine Dialog, as were all the other authors who were very problematic in the vision of the communist authorities, but not the few whom CNSAS proved after the opening of the Securitate files in 2005 to have been the institution’s “sources” of information, infiltrated among the genuinely oppositional authors. “After the investigation, I found out later, two approaches towards us were discussed: the hard line, requested by the Securitate and by some in the Romanian Communist Party, which meant excluding us from the Faculty; and the moderate position, supported by the University authorities, that we should be excluded [from the magazine] in order to break up the group, we should be sanctioned administratively and in Party structures, but we should be allowed to remain in the University, and also that we should be kept under strict surveillance. The camp that proposed ‘diplomatic sanctions’ won. The rector of the time, Barbu, had a decisive position in this respect; it is from him that I know all these details, as it was he who said that he was categorically opposed to our being excluded from the University. In the light of later developments, what very much annoyed them was that I didn’t mend my behaviour, didn’t become submissive to the regime, didn’t ‘toe the line.’ After 1983, I was no longer at the magazine, but I continued to have the contacts I had had before, which didn’t suit the regime. Worse still from their point of view, I began to have friends in Bucharest who were strongly opposed to the regime. I became very good friends with Mircea Dinescu, with Andrei Pleşu. I often went to Bucharest and we met foreign officials, ambassadors of Western countries,” recalls Alexandru Călinescu.

As a consequence of his entry into Bucharest dissident circles, Alexandru Călinescu declared his support for the signatories of the so-called “letter of the seven” that was broadcast on Western radio stations in April 1989, in which the authors criticised the re-Stalinisation of Romanian culture and the interdiction on prestigious writers, including Mircea Dinescu and Ana Blandiana. The signatories of the letter suffered as a consequence, and Alexandru Călinescu was deprived of the right to publish. That year, together with the preceding year, is very important for the history of Romanian communism, as Alexandru Călinescu recalls: “In 1988 and 1989, things became radicalised again. There began then a new wave of dissidence – declared and acknowledged as such in the Western press. The first was Dan Petrescu. Then Liviu Cangeopol. Then, in 1989, there was Mircea Dinescu’s famous interview; it was an interview that caused a great stir. As a consequence, Dinescu was forbidden [to publish]. Because, shortly after, I aligned myself with Mircea Dinescu’s position, I was forbidden too. All through 1989, basically, I was forbidden. In those last two years of communism there was a whole series of discomforts that I and my family had to bear. They are years which, I admit, I do not recall with pleasure. Especially in the last two months of 1989, I had, quite literally, the Securitate at the door. One or two cars were permanently outside the door of my apartment block. It was a very, very hard year, 1989. At school, my wife was subjected to all kinds of mistreatment. They made trouble for my son; he was already grown, a student. My daughter too, at school, was subjected to all sorts of nonsense. They also tried to upset my mother. She remained very strong; she was an admirable woman. It was all set up so that I would be intimidated, frightened, scared.” An active participant in the anticommunist revolution of December 1989, Alexandru Călinescu tried even when no one dreamt that communism would fall in Romania to maintain a high standard through the dignity of his behaviour. “I wanted to be courageous and as upright as possible in those years: at least to do that much,” he says. At the same time he modestly adds, “However I don’t compare myself with those who made much more decisive, more radical gestures.”