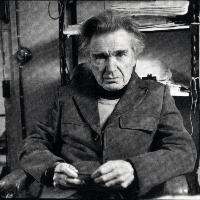

Ante Ciliga was born in the village Šegotići, near Pula, then in the province Istria, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire on February 20, 1898. A journalist, writer, politician, communist dissident and pamphleteer, he was one of the most prominent Croatian emigrant intellectuals. He attended primary school and the classics gymnasium in Mostar, and also in Pazin and Brno. He studied in Križevci, Prag, Vienna and Zagreb, where he obtained a doctorate in philosophy in 1924, and he was the first to defend a dissertation on the theme of Marxism at Zagreb University under the title O socijalno-filozofskom aktivizmu Rudolfa Goldscheida: Kritika i obrana marksizma na području filozofije (On Rudolf Goldscheid's socio-philosophical activism: criticism and defence of Marxism in the field of philosophy).

In 1918, he joined Social Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia. Shortly afterward, he became one of the founders of the Yugoslav communist movement. He was in Budapest when the Hungarian Soviet Republic was proclaimed in 1919. After the communist fiasco in Hungary, Ciliga left for his native Istria, where he organized an insurrection against Italian authorities in 1921 in an events known as the Proština Revolt. He edited and wrote for Borba, the official publication of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (1923-1925), in which he debated with Serbian communists about the national question in Yugoslavia, advocating a federalist solution. In 1924, he became a member of the Central Committee of the CPY and participated in the Third Congress of the CPY in Vienna in 1926. In the same year, due to persecution because of his illegal party work, he was exiled from the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. From there he moved to Moscow, where lectured at the Communist University of the National Minorities of the West and supported Trotsky in his struggle against Stalin. Stalin therefore had him i jailed briefly in Leningrad, and afterward, in 1930, he was sent to the Siberian concentration camps, where was released in 1935 after the Stalin-Mussolini agreement, as he had Italian citizenship. At the 4th Territorial Conference of the CPY in December1934, Ciliga was branded a Trotskyist. He also parted ways with the Trotskyists very soon, but continued to be loyal to socialist ideas. Later, in 1938, he printed his first great work, Au Pays de gran mensonge (In the Land of the Great Lie) in French, which was among the first books to inform the Western world of Stalinist mass terror. At the time, this testimony led to harsh attacks by the Stalinist CPY. After the German occupation of France, in December 1941 he departed for the Independent State of Croatia, where he was interned in the Jasenovac camp because of his suspect communist biography. After his release from the camp, he began working as a journalist for the weekly magazine Spremnost, writing articles about Soviet communism. In the final of 1944, he travelled to Berlin, whence he fled to the West, in the American military zone, before the Soviet army entered Berlin.

After the war, he lived in Paris until 1958, and prior to his return to Croatia in 1990, he lived continually in Rome. In 1954, he published his second well-known work, his memoir Sam kroz Europu u ratu (Through Europe in the War Alone). Although he had abandoned the communist movement, he continued to write about socialist ideas on the basis of democracy and to criticize party dictatorships. The whole time he cooperated with Croatian émigré communities and wrote about the Croatian national question and the general situation in Yugoslavia. He joined the Croatian National Council, which was chaired by émigré Branimir Jelić. In 1960, together with Krunoslav Draganović, Veljko Mašina and Miroslav Varoš, he founded the Croatian Democratic Parliament, which, after the conflict between Ciliga and Varoš, was called Croatian Democratic and Social Action since 1964. After 1958, he issued a bulletin under various names (Bulletin of Croatian National Council, Bulletin of Croatian Democratic and Social Action and On the Threshold of the Future) with short interruptions until 1984. In it, he dealt with the history of the Yugoslav communist movement and critically assessed Tito's regime. As a former member of the communist movement and a dissident who had transitioned into a hard-core anticommunist, he was branded a political enemy of the regime in Yugoslavia. Tito mentioned him in his paper at the Fifth Congress of the CPY in 1948, in the context of the menace represented by the “counter-revolutionary Trotskyism of Ante Ciliga”. After the communists fell from power in 1990, he returned to Croatia, where he was granted an honorary function in the commission drafting the new democratic constitution in December 1990. He died in Zagreb on October 21, 1992 at age of 94.

-

Atrašanās vieta:

- Metropolitan City of Rome, Rome, Italy

- Moscow , Russia

- Paris, France

- Zagreb, Croatia

Ion Cioabă was a Roma leader and activist who involved himself in defending the rights of his ethnic group during the communist regime and after its fall in December 1989. He was born on 7 January 1935 in Târgu Cărbunești, Dolj County. During World War II, he and his family were deported to Transnistria. After his safe return to Romania, he became a member of the Workers’ Youth League. During the 1950s he collaborated with local authorities to convince Roma people to give up nomadism and integrate themselves in mainstream society. This brought him prestige among local Roma communities and thus in 1971 he was elected the leader (bulibașa) of the nomad Roma people in Sibiu county and its surroundings. His great influence over Roma groups and his willingness to collaborate with the authorities to settle and “modernise” his nomad peers transformed him into “the best mediator between officials and Gypsies, having the ability to translate the indications or political messages into the Gypsy language, to the values and soul of the Gypsies” (ACNSAS, I 172057 vol. 1, ff. 2 f, 46–49; D 8685, ff. 305–306).

His collaboration with the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, began in 1970–1971. At that time, the Securitate organised a massive operation to collect requests for compensation on the part of those persons (Jews, Roma, Romanians) who had been deported on racial grounds during World War II. This was done in order to reclaim payments from Federal Germany. Ion Cioabă was responsible for collecting the requests of the deported Roma (ACNSAS, D 144 vol. 12, ff. 291–293). His collaboration with the secret police strengthened after his election as a member of the Presidium of the Romani International Union (IRU). He thus began to give full reports about the activity of the IRU and his meetings with its leaders, and about his contacts with other transnational Roma organisations and foreign journalists (ACNSAS, D 8586 ff. 305–306).

Taking advantage of his privileged relations with the Securitate, Ion Cioabă initiated a series of activities in support of the discriminated-against and socially marginalised Roma people in communist Romania. Alone or in collaboration with his protégé Nicolae Gheorghe, he signed memorandums that were presented to the Romanian authorities. These documents described the difficult situation of Roma people and contained a programme of measures to ease their condition through integration into mainstream society (ACNSAS, D 8586, ff. 292–297, 263–265). Moreover, Ion Cioabă joined Nicolae Gheorghe’s endeavour of demonstrating that Roma people had a distinct cultural and ethnic identity and thus deserved to be recognised as a national minority and granted similar rights to other ethnic groups. Consequently, he personally supported the organisation of cultural activities in which the richness of Roma traditions was displayed and used these examples to demonstrate that Roma people were worthy to be integrated as distinct ethnic group in Romanian society (ACNSAS, D 144 vol. 12, ff. 377–379; D 144 vol. 11, ff. 2–3 f–v; D 144 vol. 13, ff. 175–177).

Cioabă also intensely lobbied the Romanian authorities to officially endorse his and Gheorghe’s efforts to get compensation for the deported Roma. The initiative failed as Federal Germany indefinitely postponed the discussion of payment of reparations for deported Roma. At the same time, the Romanian communist regime was not willing to use diplomatic pressure against West Germany as an intervention would certainly have strained its relations with that country (D 144 vol. 12, ff. 252, 253 f–v, 291–293; D 144 vol. 13, ff. 20–21 f–v; I 172057, ff. 4–5 f–v).

After the fall of the communist regime, Cioabă continued his good relations with the Romanian authorities. Thus, in 1990 he was elected a deputy in the first democratic Parliament and obtained compensation for those Roma whose gold coins and jewellery had been confiscated by the former regime. In order to bolster his authority as the leader of Roma people in Romania, in 1992 he self-proclaimed himself “the international king of Roma.” As the files of the former secret police were gradually opened only after the establishment of CNSAS in 1999, his collaboration was never proven during his lifetime. Thus until the end of his life in February 1997, Cioabă managed to maintain a close collaboration with Nicolae Gheorghe, supporting his initiatives to alleviate the difficult situation of Roma people.

-

Atrašanās vieta:

- Sibiu, Romania

Silviu Cioată (9 iunie 1931, Ploieşti; d. 20 October 1997, Ploieşti) was a minister of the Christian Evangelical Church of Romania (Biserica Creştină după Evanghelie – one of the Plymouth Brethren Protestant denominations). He graduated Medicine in Cluj in 1956. He signed the open letter of protest against infringements of human rights in Romania relating to religious freedom entitled: The neo-protestant denominations and human rights in Romania, which was addressed to several Western embassies and broadcasted by Radio Free Europe in April 1977. For being involved in this initiative he was arrested and interrogated by the Securitate over a period of six months. From 1981 to 1982, he was involved in a network that smuggled religious literature from the West to Romania for which he spent nine months in prison (Silveșan and Răduț 2014, 63–64).

-

Atrašanās vieta:

- Ploiești, Romania

Aurel Cioran, the younger brother of Emil Cioran, was born on 14 May 1914 in the village of Răşinari, Sibiu county, Romania (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire), and died on 27 November 1997 in Sibiu, Romania. His father Emilian, a Romanian Orthodox priest, was a member of the local elite involved in the political emancipation movement of the Romanians from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His mother, Elvira Cioran (born Comaniciu) had roots in the Romanian minor nobility of Southern Transylvania. In the period 1932–1935, Aurel Cioran attended the Gheorghe Lazăr high school in Sibiu. From his teenage years, Aurel Cioran felt a strong attraction to Orthodox Christian Theology and he contemplated the possibility of becoming a monk. His brother convinced him to give up this intention. Consequently, he attended the Faculty of Law of the University of Bucharest in the period 1935–1937. During his university studies, he was influenced by the historian Nicolae Iorga and philosopher Nae Ionescu and socialised with young intellectuals such as Petre Ţuţea, Mircea Eliade, and Constantin Noica. Being influenced by this cultural milieu, he became a sympathiser of the Legionary Movement. From the 1930s onwards, he openly manifested his allegiance to the Legion and published pro-legionary articles in the Sibiu-based far-right newspaper Glasul Strămoşesc. He fostered a friendship with Constantin Noica, with whom he exchanged correspondence starting in the1960s (Sârghie 2012, 15). In 1937, Aurel Cioran started to work as an apprentice lawyer in Sibiu, and in 1940 he became a fully-qualified lawyer and was admitted to the Sibiu Bar.

In the period May 1942 to January 1944, Aurel Cioran served as an officer of the Romanian army in the Second World War. After returning home from the front he resumed his activity as a lawyer until March 1948 when he was purged from the Sibiu Bar. Due to his allegiance to the Legionary Movement he was arrested in June 1948, and convicted along with twenty-six others for conspiring against state security. He spent seven years in political prisons in Romania. After his release from prison, Aurel Cioran worked for eight years as unskilled worker and he was never again allowed to practice as a lawyer. Starting in the1960s he exchanged an intense correspondence with his brother, Emil Cioran, who had chosen to remain in France after the Second World War, and with other intellectuals such as Constantin Noica. According to Stelian Tănase, his correspondence was kept under close surveillance by the Securitate (Tănase 2009b). In 1981, the Securitate allowed Aurel Cioran to visit his brother in Paris, although this kind of permit was rare under communism in the case of former political prisoners. The strategy of the Securitate was to allow him to visit France in the hope that he would convince his brother to return to Romania in his old age. Emil Cioran’s possible return to Romania was perceived as a legitimising event by the Ceauşescu regime. The Securitate also tried to press Aurel Cioran to collaborate with them, but their attempts ended in failure (Tănase 2009b).

-

Atrašanās vieta:

- Sibiu, Romania

Emil Cioran was born on 8 April 1911 in the village of Răşinari, in the southern part of Transylvania, and died on 20 June 1995 in Paris, France. At that the time of his birth, his native province was still a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father, Emilian Cioran, was a Romanian Orthodox priest involved in the political emancipation movement of the Romanians in Transylvania. Emil Cioran had a happy childhood (Liiceanu 1995, 16) in his native village, a place which at the beginning of the twentieth century was still not changed by the rhythms of modern life. According to Ilinca Zarifopol-Johnston, the fact that Cioran was born in a historical region where Romanians had a marginal social and political position marked his personality, and this aspect strongly influenced his intellectual work because he wanted to overcome a complex of inferiority (Zarifopol-Johnston 2009, 25).

In 1924, his family moved to Sibiu, where the young Emil Cioran was already attending middle school. The experience of a cosmopolitan city like Sibiu, where Transylvanian Saxons, Romanians, Hungarians, and Jews cohabited, was important for Cioran’s intellectual formation. Here he was introduced to German language and culture, which influenced his entire intellectual work. In the period 1928–1932, Cioran attended courses in the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy at the University of Bucharest, graduating with a Bachelor thesis concerning the work of the French philosopher Henri Bergson. During his university studies in Bucharest he was strongly influenced –as were other intellectuals of his generation – by Nae Ionescu, professor of logic and metaphysics at the University of Bucharest, who had a PhD in Philosophy from the University of Munich (1919). Ionescu was also an active journalist, who shaped public opinion through his articles in the newspaper Cuvântul on key issues such as democracy, nationalism, and Orthodox Christianity. He questioned the process of modernisation in Romania based on Western political values and institutions, and criticised the democratic system, following the organicist approach of Oswald Spengler (Petreu 2016, 15–16). Nae Ionescu considered that democracy was foreign to Romanian political tradition, and displayed an anti-liberal discourse (Petreu 2016, 16–17). At the end of 1933 he became an active supporter of the Legion of the Archangel Michael and thereafter he manifested an increasingly virulent anti-Semitism.

The adjustment to the new cultural milieu was difficult for the young Cioran, who had been raised in a school system with strong German influences. The cultural elite of the Romanian capital was more oriented towards French culture, which caused him inferiority complexes. In the early 1930s, he managed to enter into the so-called Criterion group of intellectuals. Criterion was a cultural association which in the period 1932–1934 brought together young intellectual such as Petru Comarnescu, Constantin Noica, Emil Cioran, Mircea Vulcănescu, Sandu Tudor, and Mihail Polihroniade. Criterion aimed at organising lectures open to the general public on a broad variety of cultural topics. Within the Criterion group, Cioran developed lifelong friendships with intellectuals such as Mircea Eliade, Constantin Noica, and Petre Ţuţea. During his student years he published articles in the Romanian cultural press. His book debut took place in 1934 when the King Carol II Foundation published Pe Culmile Disperării (On the Heights of Despair). The book received literary awards and was a best-seller in interwar Romania, making him one of the most prominent young intellectuals. Afterwards he published several volumes in Romania: Schimbarea la faţă a României (The Transfiguration of Romania), Cartea Amăgirilor (The Book of Delusions), Lacrimi şi Sfinţi (Tears and Saints), Amurgul Gîndurilor (The Twilight of Thought).

In 1933, Cioran was awarded a Humboldt fellowship and he spent the period 1933–1935 in Berlin. During his stay in Germany, he was influenced by his readings of Georg Simmel and Ludwig Klages (Zarifopol-Johnston 2009, 84–86). He was strongly impressed by the Nazi movement, which he perceived as “vitalist”, a “solution” for the crisis of European civilisation (Laignel-Lavastine 2004, 152). Starting from the Nazi example, he considered that a similar revolution would solve the political problems in interwar Romania, a country where democracy was weakened by rampant corruption and the authoritarian tendencies of King Carol II. This experience led him to write Schimbarea la faţă a României (The Transfiguration of Romania), a book which was on the one hand a virulent critique of the social and political situation in Romanian, and on the other a call to a violent revolution and to the end of the interwar Romanian political and social system. The nationalism promoted by Cioran was different from that displayed by Romanian far-right movements (such as the Legion) because he rejected the mixing of nationalism with Orthodox Christianity and was critical of the worship of the culture of the Romanian peasantry (Laignel-Lavastine 2004, 175–176). According to Zarifopol-Johnston, Cioran’s book “reflects the country’s increasingly radical political climate in the 1930s” (Zarifopol-Johnston 2009, 92). The experience of Nazi Germany and the influence of his professor Nae Ionescu made Cioran draw close to the Legionary Movement. From1933 onwards, Cioran openly manifested his support for it through his articles in the Romanian press.

In 1937, Cioran received another fellowship from the French Institute in Bucharest, and he spent the period 1937–1940 in Paris. In the autumn of 1940, when the Legion came to power alongside general Ion Antonescu, he came back to Romania. During that period, in the course of a radio broadcast, he delivered praise to Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, the leader of the Legion murdered in 1938 by King Carol II’s regime. Due to his political involvement, Cioran was appointed in 1941 “cultural adviser” at the Romanian legation in Vichy France. He prolonged his stay in France in 1942 with a fellowship from the Romanian School at Fontenay-aux-Roses. In 1945, Cioran decided not to return to Romania and, during the late 1940s and 1950s he lived a modest life, living in student dormitories and taking meals at student cafeterias. In 1942, Cioran met Simone Boué, who became his companion for all his life. From 1945 onwards, he decided to give up writing in Romanian and chose to write in French. After the publication of his first book in French (Précis de decomposition) in 1949, he became integrated in French literary circles and he was awarded several literary prices. He continued to publish several books of essays in French such as: Précis de decomposition (1949); Syllogismes de l'amertume (1952); La Tentation d'exister (1956); Histoire et utopie (1960); Le Mauvais démiurge (1969); De l'inconvénient d'être né (1973). Although he became a famous writer in the West, Cioran avoided giving interviews to the press. Alexandra Laignel Lavastine has argued that this reluctance and his weak public reaction to the political repression in communist Romania targeting his former friends were caused by the “constant psychological threat” that his fascist past might be uncovered (Laignel-Lavastine 2004, 477, 547). According to the literary critic Matei Călinescu, Cioran tried to deal with his past by rewriting his former texts. Călinescu considers that through his 1956 essay “Un peuple de solitaires”, Cioran “wanted not only to communicate directly with his Western reader, but also to revisit his Romanian older texts in order to distance himself from them–but under the seal of secrecy” (Călinescu 1996, 207–208).

-

Atrašanās vieta:

- Paris, France