This collection of snapshots taken during truly exceptional events in the lives of all those who lived through them would not have existed had it not been for the collector’s passion for photography. Aware that he was living through an extraordinary event, whatever its ending might be, Lucian Ionică finally overcame his fear and succeeded in immortalizing images full of drama. Unanticipated either by him or by the other citizens of Timişoara, not to mention the rest of the people of Romania who heard from foreign radio stations about the revolt that had broken out in that city, the events that rapidly succeeded one another starting on 16 December 1989 came as a surprise to the majority of the population of the country. Once started, they drove many to do things that in normal conditions, out of an instinct of self-preservation, people do not do. Only someone with a true passion for photography risks his life for a dramatic image, without even the hope of wining some prestigious award for it. In 1989, Lucian Ionică’s passion for photography was already longstanding. As well as assiduously attending anticipation literature (science fiction) cenacles, he was a regular participant at the meetings of the amateur cine-clubs of Timişoara. Consequently, it was not by chance that he chose to take photographs during some of the tensest days of the Romanian Revolution in Timişoara. At that time, in the second half of December 1989, Lucian Ionică did not only want to take photographs: “Obviously I took part in the first days of the Revolution, in the crowd of people that were on the street, and I would have liked to have photographed or filmed. I had the possibility of filming at that moment. But as far as the act of filming was concerned, I was afraid. Afraid for two reasons: on the one hand, the demonstrators might see me and think I was from the Securitate; on the other hand, the others would see me and say: ‘Ah, what are you doing? Are you looking for trouble?’ In any case, filming was very risky.” The risk did not only arise from the perception of others regarding the purpose of filming, but also from the use of a bulky apparatus such as Lucian Ionică had at the time. He continues: “I didn’t film. It was riskier because it would have required much more extensive logistical arrangements than were necessary to take photographs. Filming in itself was more difficult because a reel of film – I worked with 16mm reels – was three minutes long. This meant that after every three minutes of filming the reel had to be changed. It was much harder and more complicated. I chose just to take photographs.”

The events that, by precipitation, sparked the Romanian Revolution of December 1989 were prefigured in Timişoara already on 15 December. This was the day on which, in Maria Square, close to the Reformed church beside which was the house of pastor László Tőkés, more and more people gathered to protest against the decision to evict the Reformed pastor and forcibly move him to another town. It was a Friday. The events unfolded in the second half of the day and especially towards evening. 15 December was the only day in which Lucian Ionică was not on the streets in Timişoara, as an active participant in the events. The following day, Saturday 16 December, the number of those gathered in Maria Square gradually increased until, towards evening, the amorphous mass of citizens turned into a demonstration against the dictatorship of Nicolae Ceauşescu. The key moment of this metamorphosis was when the trams passing through the square were stopped. which made all their passengers join the demonstrators. The hero who took this initiative was the poet Ion Monoran, who was a member of Timişoara’s literary Bohemia, despite the fact that he did not have a formal education as a result of his problematic past, marked by a failed attempt to cross the border fraudulently when he was a high-school pupil. Starting from 17 December, repression began against the anticommunist demonstrators, but the revolt continued during the following days, as the citizens of Timişoara held out alone in the face of repression in the hope that other cities would join their protest. “Today in Timişoara, tomorrow in all the land!” was one of the slogans chanted on the streets of the city from 16 to 22 December. All this crucial week for the Revolution was to pass before Lucian Ionică found the courage to take photographs. His decision was probably precipitated by the fact that on 21 December the popular revolt broke out in Bucharest. “I began to take photographs – not to film – in the morning of the 22nd,” he says, “after managing in the preceding days to convince a friend and a workplace colleague to come into the street with me when I was photographing. It would be safer that way, I thought at the time; and so it was. It was a form of protection, and it worked. I began to take photographs in the morning.” Later, around lunchtime, Ceauşescu and his wife left the headquarters of the Romanian Communist Party in Bucharest in a helicopter, and a few hours later they were captured and arrested on their way to Târgovişte, where there were later taken to be judged by an ad-hoc court and executed on 25 December.

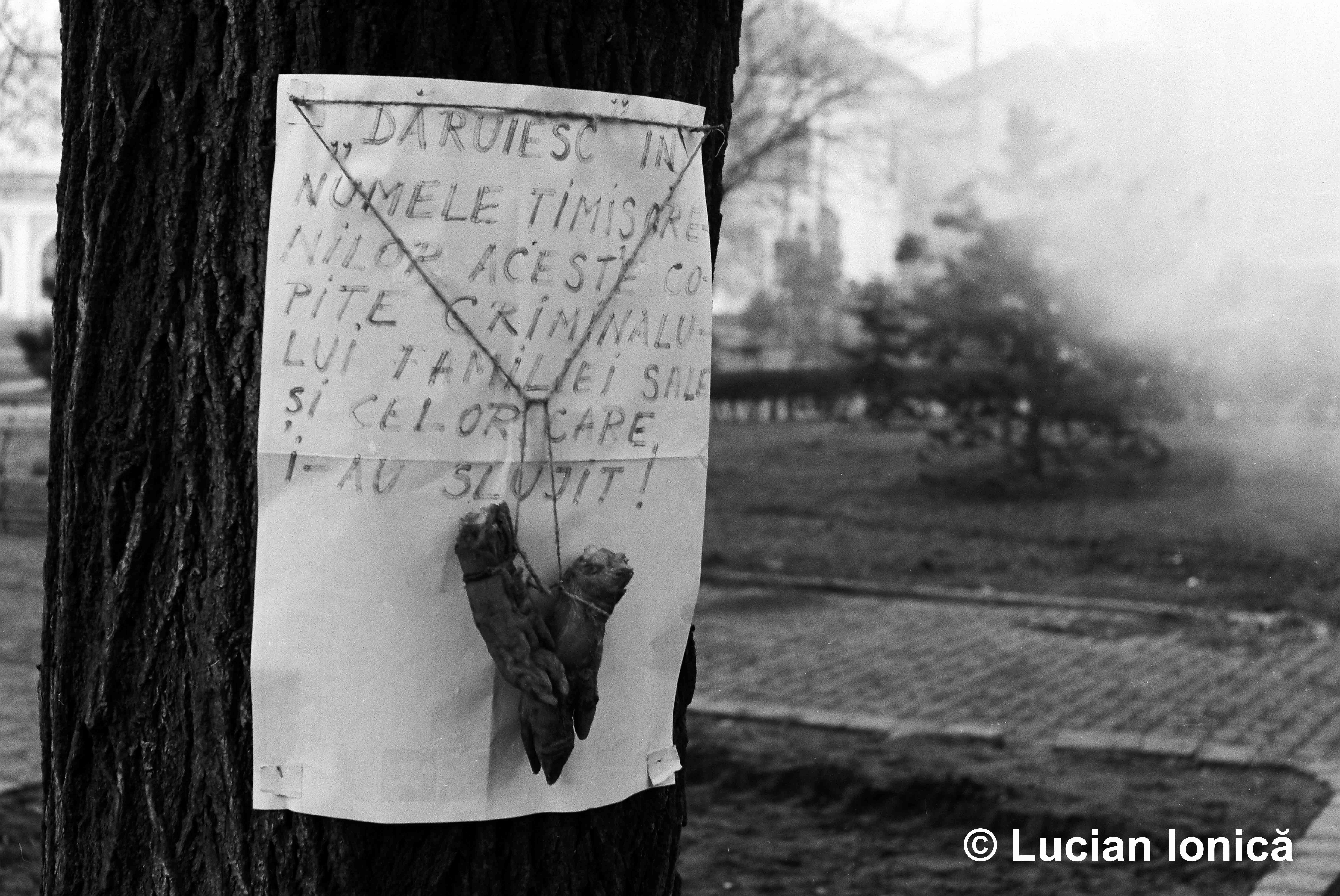

The photographs that Lucian Ionică took in Timişoara during the Revolution of December 1989 were taken in the course of three days: 22, 23, and 24 December. Most of them were taken on 22 December: exactly 101 photographs. The snapshots were taken in a number of places with a powerful symbolic resonance for the anticommunist revolutionary movements of December 1989: in the centre of Timişoara – in Victory Square, in front of the Opera, and in Liberty Square, at the Paupers’ Cemtery, at the County Council, and at the Central Railway Station. The greater part of the images are from the present Victory Square, which was probably the most significant place connected with the moment of the victory of the Revolution. A few photographs, very moving, were taken inside one of the Timişoara hospitals where the wounded of the Revolution were brought – adults and children alike. With a few exceptions, the photographs were taken on the ground, at the level of the crowds or of the clusters of demonstrators. They were taken with a Praktika MTL3 cameral, made in the DDR. At the time, this was one of the best cameras that could be obtained from communist shops – but only if one had a special relationship with the salesperson, because such products were imported in very small numbers, with the result that the supply was always well below the demand, and they were only sold “under the counter” (or “under the hand” as the Romanian expression went at the time). The photographs were all black and white, as colour film was a rarity under communism. Lucian Ionică processed and developed the photographs himself, in his personal laboratory. The negatives of his snapshots of the Romanian Revolution were stored in his home.

The more than 100 prints and rolls of film containing the greater part of the private collection of images of the Revolution of December 1989 in Timişoara in the possession of Lucian Ionică remained for a long time in his own home, and had no public impact. “For a long time after I took them,” he says, “they lay quietly in a box, in my home, in what I might call a private archive. They remained there for years, because, as I saw it, there was no sufficiently powerful context for them to be taken out in public.” It was only in 2014, on the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Revolution, that about a third of the photographs were displayed in a public place, as part of an exhibition that aroused a significant response in Timişoara. Later they were moved to another public place, the Memorial to the Revolution in Timişoara, where they now have the status of permanent exhibits. The original rolls of film, together with the original prints developed from these remain in the private dwelling of Lucian Ionică.