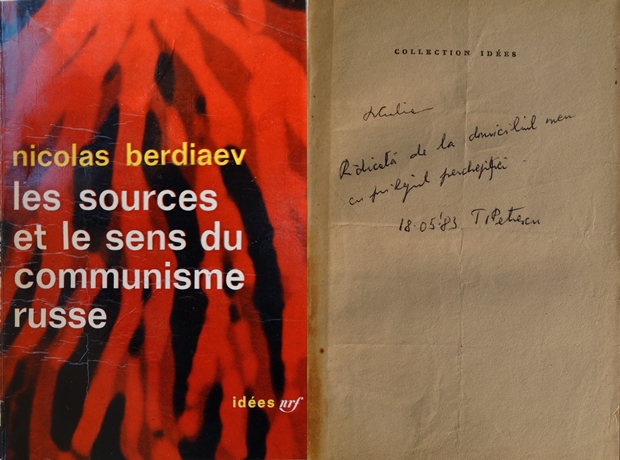

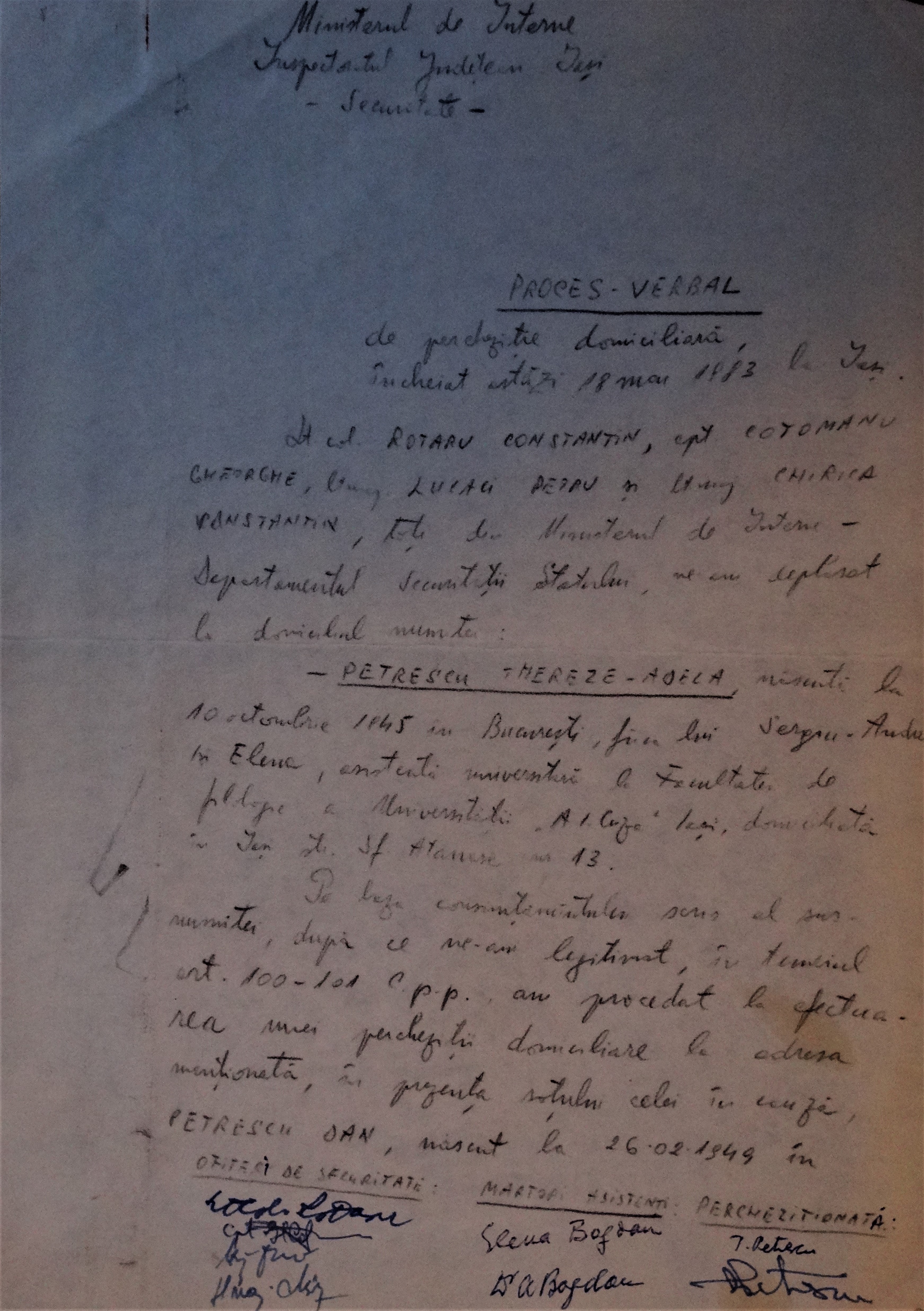

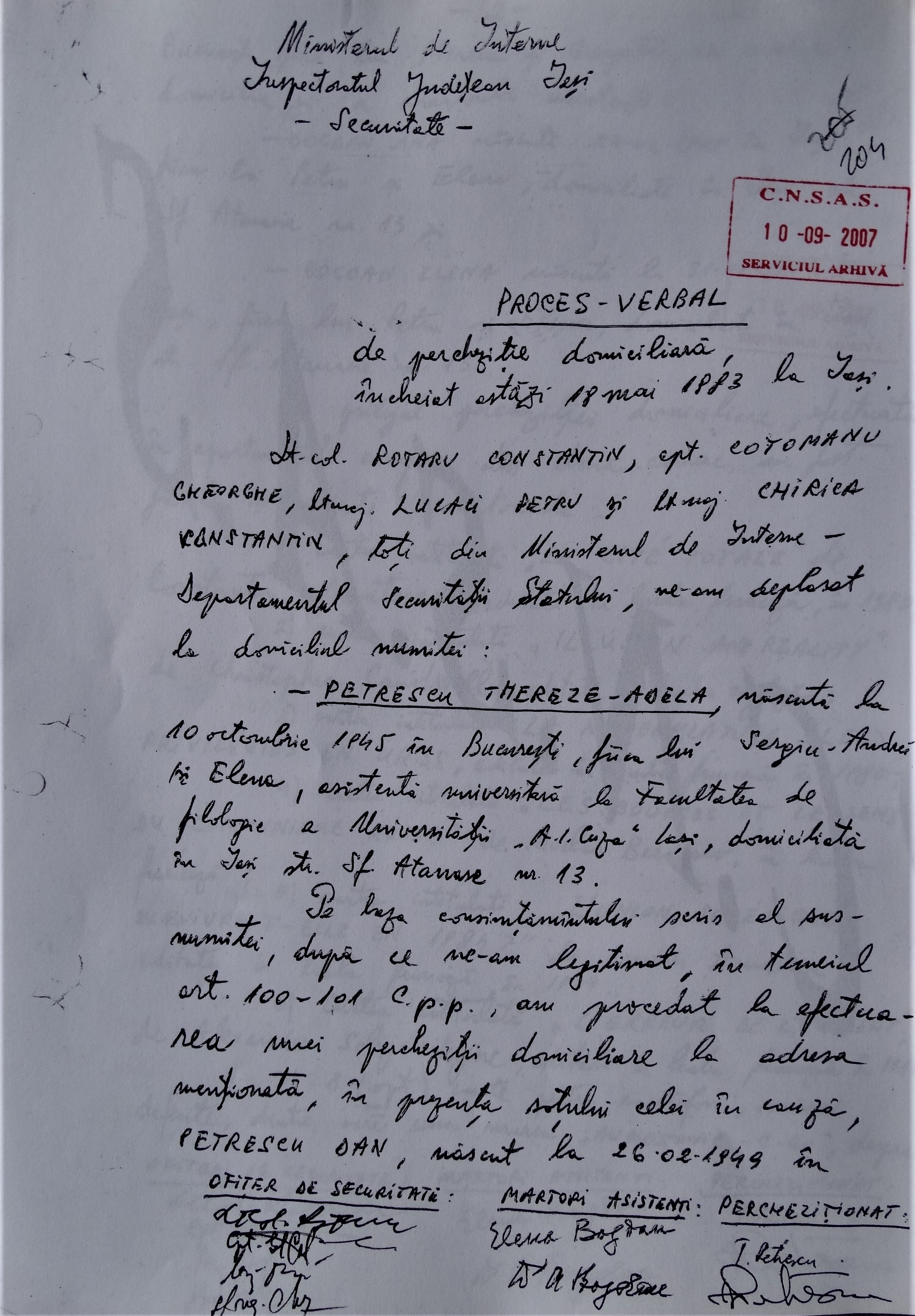

The document that records the extent of the search carried out at the home of the Petrescus on 18 May 1983 is in the family’s private collection in an original copy, made out by the officers who took part in the event. Another two copies were kept by the communist authorities of the time. The minute records that the Petrescus were present at the search, as were two witnesses. It consists of four pages, very clearly written, and is made out in the name of the Iaşi County Inspectorate of the Securitate. Each page is signed both by the representatives of the forces of control and repression and by the witnesses and the couple themselves. The document lists the objects that were kept by the Securitate on this occasion: books; audio cassettes, including one containing a recording of Virgil Ierunca’s broadcast on Radio Free Europe in which he highly praised Dan Petrescu and other young intellectuals in Iaşi for their articles in the student magazines Dialog and Opinia Studenţească; rolls of recording tape; photographs; letters from various people; pages of notes; and a folder labelled “Furrows across the baulks – feuilleton novel of the collectivisation,” containing forty-five leaves of the manuscript of this collective novel. Among the books confiscated were some that later became classic works of critical analysis of the communist system, but which were very recent publications at the time, for example La Nomenklatura, les privilégiés en URSS by Mikhail Voslensky (1980) and L'Union soviétique survivra-t-elle en 1984? by Andrei Amalrik (1977). There were also critical works on Romanian communism published by Romanian writers in exile, such as La Cité totale by Constantin Dumitrescu (1980). The couple managed to save some books from confiscation, but of those removed from their home by the Securitate only one was given back to them, though it is not clear on which criteria this particular book, Les Sources et le sens du communisme russe by Nikolai Berdyaev, was returned – perhaps because it dated from 1938, so was much older than the others. Thérèse Culianu-Petrescu recalls how they managed to hide some of the most critical, and implicitly the most incriminating books: “The next day, 18 May 1983, at six o’clock sharp in the morning, the guys burst in. […] At first they were very pleasant. They gave us time to get dressed, and those minutes gave us a chance to remove some books, to give them to my aunt, who stuck them under her jacket, under her overcoat. Solzhenitsyn, for example. We saved the Gulag and a few others. My aunt took them into her room, where they had no mandate to enter and where they didn’t think of entering. [… Wherever they had a mandate,] they left nothing untouched. Nothing, nothing. You realised that you could hide something anywhere, in the garden, in the house, in the woodshed, and they would rummage around and they could find it. They were capable of moving everything, of going through everything.” And regarding the immediate consequence of the search, interrogation at the Securitate headquarters, she adds: “The search lasted approximately five hours. From six in the morning to eleven. […] Then they took us up – ‘up’ meaning to the Securitate. It was on a street named Triumfului. Now after 1989, the gangs of Securitate people have built a district of apartment blocks that they own.” Dan Petrescu adds, with regard to the manner in which those who came conduct the search acted in order to find what interested them, underlining that the Securitate was particularly interested in a cassette with the recording of a Radio Free Europe broadcast, in which some young Iaşi writers had been highly praised, among them himself, and in the manuscript of the collective novel: “They had come on the basis of information, for they were looking for certain things. They were looking for a recording of a broadcast on Radio Free Europe where [Virgil] Ierunca praised us and… they were looking for books […] They confiscated a lot of books from us. Only one was given back to us, after the search. Berdyaev – his book about the sources and the meaning of communism. At the same time they asked me about the novel [“Furrows Across the Baulks” revisited]. I said to them: ‘Why are you still looking for it? Because you’ve already got it.’ They had taken it from George Pruteanu. […] It didn’t exist in more than one manuscript. There were no copies. It passed from one to the next and each one added to it. They were also looking for letters in the search.” Dan Petrescu adds, to give a clearer picture of those months, another detail that casts a new light on that moment: “The search took place, at our home, in May 1983. In March, I found out later in documents at CNSAS, the Securitate guys had made new recruits in literary circles in Iaşi. Ten new names. In editorial boards of periodicals, publishing houses, that sort of thing.”