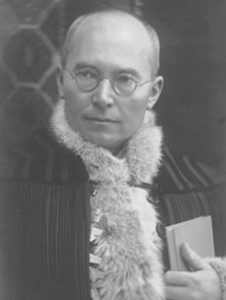

Friedrich Müller (also known as Friedrich Müller-Langenthal) was bishop of the Evangelical Church of Augustan Confession of Romania during the period 1945–1969. He was known as an uncomfortable ecclesiastical personality for the communist regime; this is why the Securitate attempted, unsuccessfully, to eliminate him in the 1950s. Bishop Müller was one of the bishops who opposed the limitations imposed by the communist regime on the practice of catechisation of children and young people for their religious confirmation. He is the author of many documents in the High Consistory Collection which illustrate this opposition.

Friedrich Müller was born on 28 October 1884 in Valea Albă/Lagenthal (now in Alba county, Romania) in a peasant family and, because his parents died when he was very young, he was brought up by richer relatives. After finishing high school in Sibiu, he studied physics, geography, and theology, and then history, geography, and theology at the universities of Leipzig, Cluj, Vienna, and Berlin (1903–1909). Given his complex intellectual background, the High Consistory made him counsellor for denominational schools in the interval 1922–1928. In 1932, he failed to occupy the position of bishop. However, the same year he became episcopal vicar. Between 1940 and 1944, the Evangelical Church A.C. of Romania came under the control of the local Nazi movement. In this context, in November 1940, Müller opposed the taking-over of denominational schools by the German Ethnic Group in Romania, an organisation controlled by the local Nazis, which managed every aspect in the life of Germans living in Romania (Traşcă 2011, 324). Prior to this moment, however, Müller had displayed no anti-Nazi attitudes in the community. On the contrary, he made a few pro-Nazi public statements in the late 1930s. After 23 August 1944, when Romania joined the Allies in World War II, the pro-Nazi bishop Wilhelm Staedel was demoted. The episcopacy became a source of conflict between the former Bishop Viktor Glondys, forcefully removed by the Nazis, and Friedrich Müller, who argued in support of new choices. Müller was elected bishop in April 1945 following the church elections. At this moment the situation of the Evangelical Church A.C., and indeed that of Transylvanian Saxons in general, was very difficult. According to a report of the High Consistory, there were 229 active ministers in 1943, but the number had dropped to 122 ministers by 1945 (Müller 1995, 21). The deportation of ministers to the USSR and the arrests carried out by the Securitate were the main causes for this decline. The deportation of the adult Saxon population from Transylvania to the USSR and the confiscation of their property led to the massive poverty of church parishes. Despite this difficult situation, the church’s authority increased as it was the only institution of importance for the Transylvanian Saxons which had not been suppressed in the period 1944–1945.

Friedrich Müller proved to be an uneasy bishop for the new political regime due to his opposition to the interferences of the state authorities in the domestic affairs of the church. For example, in the period 1949–1951 he tried to prevent the election of pro-communist members to the High Consitory or to local presbyteries. As Leslie László has observed in the case of Hungary, the Presbyterian system of the Protestant churches, allowing a “greater lay representation” in their elected assemblies, represented a favorable institutional context for the infiltration of these synods by the secret police (László 1989, 144). This is why in 1952 the Securitate planned his removal from the episcopal chair in order to promote a more servile minister. Although the plan was prepared in detail and sent for approval to the leadership of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Securitate did not receive a positive answer to its request. A plausible explanation for this decision is the good personal relations that Friedrich Müller had with Petru Groza, the prime minister of the communist-dominated government. In spite of these attempts by the Securitate, Bishop Müller managed to maintain a dominant position within the High Consistory until the 1960s. Although he tried to stop the interference of state institutions in the internal affairs of the church, Bishop Müller proved concessive in other issues and supported some policies of the communist regime such as the collectivisation of agriculture. The most intense conflict between the Evanghelical Church A.C. and the communist authorities was caused by the opposition of the church leadership to the banning of the confirmation classes by which ministers prepared children and young people for religious confirmation. Taking into account that the communist state and the Evangelical Church A.C. tried to find a modus vivendi during the episcopacy of Friedrich Müller (1945–1969), this relationship could be labelled as “accommodative” in Sabrina P. Ramet`s classification, in which, the “accommodative mode” of state-church relations in the Soviet Bloc “involves compromise on both sides – sometimes mostly on the Church’s side” (Ramet 1991, 83).